This page will host initial meditations on our seminar keywords which are starting points for discussions. These are generally presented at the end of seminar to preview the following week’s discussion and readings. Keywords currently composed by me (Neel), but let me know if you’d like to contribute or write one of the upcoming keywords.

Jump down to keywords:

1) planetarity, matter, study

2) earth

3) anima

4) affect, security

5) atmosphere, carbon

6) human, intimacy

7) relativity

INTRODUCTORY PRESENTATION, 9 JANUARY 2015

Keywords: planetarity, matter, study

This seminar will introduce basic themes and contemporary debates in postcolonial studies; it will also begin an exploration of several keywords related to emerging critical discourses we might call ‘posthuman’ due to their focus on the political and ethical relevance of nonhuman physical matter and life that seems to exist beyond the sole control of human social formation. These posthuman discourses attempt to make sense of the worlds of bodies, environment, technology, animality, and affect which help to assemble material environments and the forms of power we encounter in everyday life. Our lectures and readings will enter through posthuman questions and then turn an eye to how such issues are handled by scholars of colonialism, race, and indigeneity. So we will do things perhaps in the reverse order of what you might expect; instead of beginning with the foundations of postcolonial and posthuman studies and moving forward to contemporary articulations, we will jump in and begin with contemporary crossings of the two fields and then loop back to the foundational concepts, texts, and histories.

So let’s begin with some very current questions. I want to begin our first meeting by sharing two images from the past decade that raise the connection of the human and the planet by focusing attention on anthropogenic climate change. From my perspective, these images capture something of what I hope to articulate via the seminar title ‘Planetarities,’ a conjunction of two concerns: (1) the more-than-human assemblages of life, energy, and matter that form the background of contemporary and historical forms of power and social relation, and (2) ongoing analysis of humanity’s unequal relations of wealth, labor, and life produced by systems of colonialism and capitalism.

Planet-feeling, according to postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak, is an experience of the uncanny, the unheimlich, the undoing of a sense of habitation or settlement — and these images draw affective power from that phenomenon.

The first image is a news photo of a work of performance art. The ‘climate cabinet’ was an official meeting of the government of the Indian Ocean nation of Maldives, which was staged as a press event to pressure delegates at the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit to pass an agreement including assistance to the countries experiencing climate disaster. As the lowest-lying country in the world, Maldives is the nation most endangered by rising seas; the IPCC predicts a two-foot sea level rise, which will make the country virtually uninhabitable by 2100. Prior to the cabinet event, the Maldives government made two major decisions related to climate: it pledged to become carbon-neutral by 2020, and it established an investment fund to raise money for the eventual relocation of the entire nation to higher ground, perhaps in India or Australia. In the absence of a global climate agreement, the political discourse of climate change is largely focused on adaptation rather than mitigation, and unrealistic enthusiasm for adaptation is deflated in the state’s performance of underwater theater. The ironic image of the cabinet’s ‘adaptation’ to climate change in scuba suits portrays both the human body and the sovereign — the governing authority — as literally swamped by the geophysical agency of the planet.

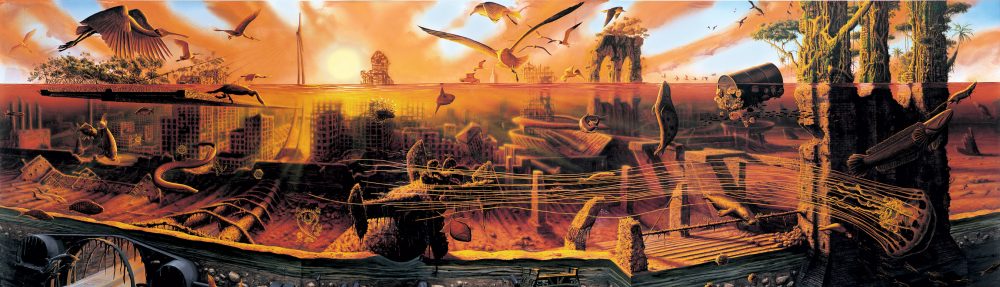

The second image is a landscape by the noted New York painter Alexis Rockman (see the banner of this website). It depicts the borough of Brooklyn 3000 years in the future, when an environmental disaster has submerged New York, which is now populated by birds, jellyfish, and ruins — no humans, though. Rockman playfully titles his 2004 work Manifest Destiny — figuring environmental destruction as an endpoint to the settler colonial project that transformed indigenous Lenape land into the seat of US empire. Rockman explicitly draws heavily on the settler romance of the indigenous landscape, integrating influences from the 19th century Hudson River School of landscape painting (particularly Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire and Albert Bierdstadt, “Storm in the Rocky Mountains”) into his vision of an environmental blowback that marks the end of man’s empire over nature.

Both of these images communicate an immediacy of crisis through spectacles of destruction. Imagining the end of human settlement and a posthuman future literally devoid of human bodies suggests the urgency of acting to mitigate environmental change in the present. And yet, in the image of a humanity swept away by the geophysical agency of the planet, there is also something obscured — the everyday character of environmental violence, the slow violence of bodies colliding across scales and species, the long processes of migration, colonial settlement, social reproduction, and ecological destruction that gave form to that abstracted figure of species we call ‘human.’ Is there an aesthetics or a politics that can capture the simultaneity of these two pressures on the figure of the human, one animated by the apparently ‘external’ physical forces of matter, life, and planet, and another consisting of fractured ‘internal’ social worlds of a differentiated human, of culture, society, and political economy?

In the face of the risk that the spectacle of extinction, the fear of crisis, will swamp the political intelligibility of the many small and intricate processes that constitute global climate change and other forms of ecological violence, this seminar highlights the planetary as a figure of potential for uniting and also transforming two perspectives that might at first appear at odds in the interpretation of these two images. On the one hand, we have the perspective of the posthuman, a perspective looking outward from a figure of the human threatened by the blowback of its own destructive practices of imperial development. On the other hand, we have the perspective of the postcolonial, a perspective that would restore a sense of history and social difference to identify the racial, colonial, and gendered violences that created settler forms of life and embedded them in specific ecologies and geographies.

In the academy, these perspectives often appear at an impasse. Take, for example, one of the early essays staking claim to a postcolonial perspective on environmental questions. Focusing on the specific movement in US environmental activism known as deep ecology, the liberal Indian historian Ramachandra Guha’s 1989 essay “Radical American Environmentalism and Wilderness Protection: A Third World Critique” presents the impasse as such: “despite its claims to universality, deep ecology is firmly rooted in American cultural and environmental history and is inappropriate when applied to the third world.” There is much to be said for Guha’s position, which is supported by a history of orientalist depictions of the peoples, animals, and landscapes of the darker nations as well as the negative impacts on indigenous lifeways caused by colonial and neocolonial conservation policies. And yet from another perspective, Guha’s enclosed national cultures of environmentalism seem to obscure local complexities and transborder connections, risking his own form of orientalism by suggesting unsurpassable cultural divides. Twenty-five years after Guha’s essay, the maturing of a domestic environmental justice movement in the US, the strengthening of first nations’ land activisms against mineral and fossil fuel development, and a variety of emerging state policies on carbon use, development, and the exploitation of animals across the global south challenge the conception of environmentalism as a singular or even a north-dominated enterprise.

For example, UNC anthropologist Arturo Escobar has documented how Latin American states have begun new conversations about sustainable design, ‘good living,’ and ‘the rights of nature,’ which attempt to combine the development of socioeconomic equity with ecocentric concerns. And more provocatively, geographer and race theorist Arun Saldanha shifts the focus from environmentalism to the racial formation of the carbon economy itself; he characterizes climate change as a racial assemblage of colonial capitalism, one that requires a politics that confronts the racial violences of colonial humanism. He writes in his manifesto “Some Principles of Geocommunism” that

Hegemonic Western humanism believes firmly in the progress of knowledge, technology and colonisation. The implications for the rest of life have been an afterthought. The ecology of global capitalism has for some four centuries been intrinsically racist, making white populations live longer and better at the expense of the toil and suffering of others. Humanitarian campaigns after ‘natural’ disasters in the South (the 2010 Haiti earthquake), disasters which will become routine if capitalism goes on as it does, are the clearest example of the continuing racist hypocrisy underneath Western humanism. For the truly rational humanist response to such disasters is to prevent them, to change the economic structure making brown and black populations die in disproportionately large numbers where extreme weather, drought or earthquakes strike. As activists point out, places suffering most from climate change have contributed least to carbon emissions. The Anthropocene [the present geologic era dominated by human-induced changes to the climate] is in itself a racist biopolitical reality.

While Escobar and Saldanha pursue a politics to undo forms of colonial humanism that posit the social world as radically detached from ‘nature’, such a move is complicated by the fact that neoliberal crisis thinking often makes an idealist turn toward the material worlds of animals, bodies, and the planet in ways that foreclose attention to difference and inequality within/across human social groups. For example, as we consider next week’s readings on the keyword ‘matter,’ we encounter statements from Jane Bennett and Timothy Morton that argue for analytically setting aside the worlds of the human in order to enliven nonhuman objects in the domains of politics and aesthetics. While these two authors offer different approaches that we must evaluate independently — Bennett (following the actor-network theory of science, technology, and society scholar Bruno Latour) sees the political ‘actancy’ of nonhumans as enlivened by their networked relations that include humans, while Morton’s speculative realism argues against placing things in relation in order to gain critical intimacy with those objects — they each stake a claim to a kind of realism of the objective world which they attempt to access outside the world given by anthropocentric discourses.

Do such theories, while admittedly overturning a longstanding anthropocentrism in philosophy, cultural studies, and political theory, ultimately shore up a human/nonhuman binary, repeating the humanist conceit that it is possible to extract human from interspecies connection? The same question might be asked of the concept of the anthropocene, which suggests that something called the human becomes the primary agent controlling the geophysical formation of the planet. We could, of course, argue instead that a handful of wealthy countries that have longest exploited fossil fuels are responsible for climate change — not the human species writ large. Furthermore, turns to the analytic object of the nonhuman in work on speculative realism, object-oriented ontology, animal studies, environmental humanities, etc. seems to go against a different strain of posthuman thinking represented by feminist science studies scholarship, which suggests that there simply is no such thing as an independent human body, that we are radically interspecies in our embodiments and networks, imbricated in a complex field of life and power. Think, for example, of the millions of gut bacteria occupying our entire alimentary tract from mouth to anus — our very bodies exist only as interspecies assemblages.

Further, could the idealist move toward an ‘outside’ of the human reinstantiate Guha’s concern about the dynamic of orientalism, classically described by Edward Said as creating a phantasmatic identity of the Western human by producing the ‘Orient’ as an externalizable, affectable, animalized other? Is racialization itself the condition of possibility for turning to the ‘outside’ of the human? Denise Silva has recently argued that the tools of scientific rationality established in the colonial Enlightenment rendered the racialized subaltern as an outer-determined, affectable subject, one fixed by the physical relations of body/nature as opposed to the fully-human European subject who can reason and thus transcend nature and universalize his interests. Donna Haraway once pressed us to consider that such racial processes unfold in contemporary scientific posthumanism by diagnosing the field of primatology as ‘simian orientalism,’ a field that constructs the simian relation to the human as simultaneously origin and other. Today, power assemblages such as the war on terror and biosecurity seem especially comfortable reproducing colonial divisions of labor and life through posthuman bio-technical interface. Are today’s critical and political turns to environment, animals, objects, and things thus implicated in a form of what we might call ‘object orientalism’? If so, what other methods or starting points exist for thinking together the human and the planet without insistently invoking the nature-culture binary?

This is a huge question that we will take up via different keywords and areas of scholarship relating to human/nonhuman relations throughout the semester. One area we can begin to think through these questions is by distinguishing different approaches to conceptualizing what we mean by matter or the material world. We will introduce foundational takes on historical materialism from critical political economy (Karl Marx) and the philosophy of immanence drawn from the biological sciences (French philosopher Giles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Felix Guattari). Later, we will explore theories of affect, significant in postcolonial and feminist theories, which suggest another domain of materiality based in the sensorium of living bodies and the interactivity of living and nonliving bodies. Another important materialism, the quantum materialism of particle physics, today has some resonances with feminist and critical race theories; this is mentioned in the reading by Morton for next week and it is an optional topic we could explore depending on participants’ interests.

As we critically attempt to unravel what we mean when we talk about the physical, material world, including the worlds of bacterial, animal, and plant life and the planetary geologic materialities of rising oceans and warming atmospheres, we will attempt to situate matter within the international divisions of labor, wealth, and life that have formed the primary concerns of academic Marxism and postcolonialism. Put more simply, we will consider how the material world is itself harnessed as a force in creating and sustaining colonial inequalities. As such, this semester we will explore the internal tensions and debates within posthuman and postcolonial approaches to matter and the human; view recent art and design that develops new aesthetics for articulating human entanglement with nonhuman matter and life; consider how histories of colonial and racial violence take form in the supposedly ‘nonhuman’ worlds of objects, animals, territories, and technologies; and engage in collective discussions and research projects that will critically examine histories of and investments in the figure of the universal human.

These activities will explore conversations and debates that are still emerging. As you can see from the proposed schedule, the rest of the semester we will take up the question through different objects and permutations, moving from the basic idea of matter to the problem of earth, the question of the animal, and the problems of security, atmosphere, and carbon as they transform political dynamics. As we’ll discuss later today, you will have the opportunity to revise or add terms to this list and to suggest specific directions we might pursue posthuman/postcolonial connections. In all of these discussions, even as we move past exclusively human social worlds, and even as we attempt to offer a critical perspective on power, we will find that the human and the colonial remain at the center of concern. As such, I want to propose on our first day that we bracket the prefix ‘post’ that attaches to the terms ‘postcolonial’ and ‘posthuman.’ Even though these are the dominant terms in the academy, we still live in a world created by colonial forms of exchange and territoriality, evident in the local struggles we encounter here in North Carolina over environmental justice, native claims to land and state recognition, and fights over who has access to the university. Ecological and economic crises that manifest in neoliberal North Carolina raise the question of whether it makes sense to think that we are ‘beyond’ the colonial or the human. Instead, the present crises require what we might call strategies of decolonial inhumanism, tactics for unraveling histories and structures of colonial modernity that mask unequal assemblages of power through abstract visions of human rights, freedom, and development.

One significant issue we face is that the neoliberal focus on crisis — the idea that the world is suddenly falling apart, that economic, ecological, and political systems are suddenly breaking down — is itself an attempt to govern us through emotion, to create anxiety and force us to capitulate to neoliberal processes for externalizing losses and wastes of capital, to accept that individuals and the public at large must pay the price for limited growth and for precarities of labor and environment. The crisis situation is in fact not so new to postindustrial working classes or to entire national populations of countries whose economies and social states were decimated by neoliberal reforms from the 1970s-1990s. In an assessment of the economic decline of US empire, Radhika Desai suggests that the 2008 world financial crisis is actually a late stage of a broader crisis of American financial empire that emerged in the late 1970s. At that time, the US-led International Monetary Fund forced states of the global south to bail out the imperial financial system and to repay defaulted loans to northern banks who had made speculative development loans. While the IMF’s policy of neoliberal structural adjustment that devastated the social systems and economies many countries across the south bailed out US-led finance capital, neoliberal reforms domestically in the US later expanded predatory lending and eventually brought home the housing crisis leading to mass unemployment and stagnation that had already taken hold in many other parts of the world and in minority communities at home since the 70s.

This sheds some light on the keyword of ‘study,’ and the feeling of crisis in the university that Moten and Harney reference in “The University and the Undercommons” (our first reading). The US university had been relatively well funded in the 90s and 2000s (when the global south had bailed out northern banks to sustain neoliberal regimes of speculation); after 2008, the economic downturn was paired with a right-wing takeover of budgets which shrunk the tenure-line academic workforce in favor of flexible and precarious adjunct labor. This is already a familiar story to you. And yet universities are expanding graduate education, are intensifying the split between tenured faculty and incoming Ph.D.s who are more and more likely to remain precarious laborers throughout their careers. Critical thinking is a commodity to be expanded in large writing programs, which is why Moten and Harney call it the counterinsurgency of the university, the circling of its maroon community (including grad students). Tenured faculty, department chairs, and deans intensify this problem when they try to maintain large graduate programs to satisfy faculty teaching desires, create new revenue streams, and maintain national rankings; in this environment, it is no surprise that graduate students increasingly seek out professionalization (per Harney and Moten, they refuse to refuse professionalization, refusing the university’s own call to center itself), while faculty double down on the teaching of content under the illusion that they ‘know the field’ which they see as critically oriented against social power.

For this reason, one could reasonably suggest that the traditional graduate seminar based on lecture, discussion, and papers is at best no longer suited to grad student needs and at worst a jealously guarded privilege of tenured faculty whose low teaching loads and specialized courses are dependent on the mass precaritization of academic labor. The academy may not at present structurally equipped to articulate a critical challenge to neoliberalism on its own terms. In fact, Harney and Moten’s essay might suggest that my own choice to assign their essay simply fulfills the prophecy that “The sovereign’s army of academic antihumanism will pursue this negative community into the undercommons, seeking to conscript it, needing to conscript it.”

The problem that Harney and Moten outline asks critical intellectuals whether their critiques grapple with the labor conditions that enable their own apparently ‘resistant’ stance as professionals in the academy. It is somewhat different from Latour’s sense that critique is exhausted — which seems to suggest that because oil companies distrust scientists and because imperial war planners ocasionally use our terms (deconstruction, war machine) that they have actually coopted critique itself. I find Latour’s interest in building something rather than destroying it useful, but wonder if his own sense of the crisis of critique is an effect of neoliberal crisis governmentality rather than a challenge to it. Isn’t this exactly what governments say when they argue for practical education that attempts to manage students as consumers?

That is a dynamic we perhaps can’t escape. But at the very least I offer to open up part of the syllabus and the design of the assignments to your input. Of course, you may refuse this as well (as it outsources more of my labor to you). We’ll discuss it more in a moment. Think about what would be most useful for you to do as an assignment. If it’s writing a traditional seminar paper, that’s fine. But we also might be able to produce something like a collaborative website explaining key convergences of decolonial/inhumanist thought and activism to other audiences; a mini-workshop; or a manifesto that includes our individual interests but uses collaborative frameworks to produce something else. Or you all might be able to do different kinds of projects best suited to your needs and interests.

MEETING #2, 16 JANUARY 2015

Seminar Review: Our first week’s readings covered the topic of ‘matter’ and introduced some precepts of actor-network theory (Latour, developed by Bennett), speculative realism (Morton), and the Spinozist-Deleuzean tradition of vitalism, which reconceptualizes bodies by attending to life as a field of immanent potentials. We discussed some differences between Bennett’s interest in relationality between networked objects and Morton’s insistence that we suspend relationality to grasp the uncanny object, allowing us to understand life as internal to objects (including hyperobjects that are massively distributed in time and space). Finally, we queried whether a more traditional historical materialism proposed by Marx should be dismissed so quickly as anthropocentric. We reviewed Marx’s call for a history of human technologies, his attention to capitalism as a process that alienates labor and extracts unsustainably from natural systems like soil. We zeroed in on the difference in machines in Marx and Deleuze and Guattari, taking note of D&G’s critique of an idea of representation that would separate form from content. Rather than viewing the realm of representation as a superstructure of bad faith that must be unmasked by attending to the base of political economy, D&G argued that materiality needs to be given its own complexity of expression by understanding its forms of becoming and striated structures of assemblage. I ended the class by suggesting that some of the turns from human to nonhuman remained untheorized in terms of the status of the human, and that this problem (reflected in an orientalizing impulse in several of the readings) was thematized in D&G’s passages on rhizome and nomad.

This was a complex and wide-ranging discussion that sets up our readings on the keyword ‘earth.’ This next keyword unites longstanding questions in postcolonial theory with our concerns about materiality, objects, and indigeneity. Briefly, one could characterize the practice of antihumanist postcolonialism in the academy as a relatively short-lived affair, one opening with Edward Said’s Orientalism in 1978 and transitioning into another set of projects around the years 1999-2000, when a spate of books by authors including Dipesh Chakrabarty, Gayatri Spivak, Walter Mignolo, and Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri developed a set of meta-critiques of postcolonial knowledge production. These were already diverse critiques that reflected the multiple disciplines (especially literature and history) and geographic foci (consider the differences between South Asian and Latin American subaltern studies groups). The idea of a ‘beyond’ of postcolonial studies (Loomba, et. al.) became an almost obsessive refrain in the early 2000s, and coincided with attempts to geographically and temporally broaden the scope of postcolonialism’s theoretical lineage and objects of analysis. In opposition to the totalizing tendencies of globalization theories of the 1990s,a number of postcolonialists began to turn back to reviewing anticolonial theoretical lineages.

Keeping the constant processes of field-reframing in mind, our four readings glimpse the turn to planet in the context of shifts both within postcolonialism and in the humanities more broadly. They also allow us to look back to earlier anticolonial theory to reframe present debates. Commenting on the late reception of postcolonial studies in France and a misleading manifesto against it by French political scientist Jean-Francois Bayart, Robert Young offers a dizzying array of roots for anticolonial analysis and action crossing Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa:

Strange as it may seem, the anticolonial theory from which postcolonial studies has developed was not just French: setting aside other European anticolonialists other than Sartre, such as Bartolomé de Las Casas, Edmund Burke, Karl Marx, V. I. Lenin, or J. A. Hobson, a list of the genealogy of postcolonial theory would include the writings, in no particular order, of Simon Bolivar, José Martí, José Carlos Mariátegui, the Tupamaros, Carlos Marighella, Subcomandante Marcos, Daniel O’Connell, Michael Davitt, James Connolly, Countess Markievicz (Constance Gore-Booth), Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Duse Mohamed, Mohammad Hassanein Heikal, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, James Africanus B. Hortus, J. E. Casely Hayford, Lamine Senghor, W. De Graft Johnson, Jomo Kenyatta, Cheikh Anta Diop, Ousmane Sembène, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Julius Nyerere, Mario de Andrade, Amilcar Cabral, Olive Schreiner, Solomon T. Plaatje, Nelson Mandela, Joshua Nkomo, Zanele Dhlamini, Steve Biko, Marcus Garvey, George Padmore, C. L. R. James, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, W. E. B. DuBois, Sri Aurobindo, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Mohandas K. Gandhi, Annie Besant, M. N. Roy, Sarojini Naidu, Bhagat Singh, Aruna Asaf Ali, Subhas Chandra Bose, B. R. Ambedkar, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sun Yat-sen, Mao Tse-tung, Ho Chi Minh, General Vo Nguyen Giap, Zhou Enlai, Lin Biao, D. N. Aidit, Ti Kooti, and Donna Awatere. Some of them wrote in French. Many others did not. Bayart mentions the international colonial organizations; I would rather be interested in the international anticolonial organizations, particularly the Universal Races Congress (1911), the Internationals (1919 – 35), the Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East (1920), the Congress of the Toilers of the Far East (1922), the League Against Imperialism Congress (1927), the Fifth Pan-African Congress (1945), the Asian-African Conference (Bandung) (1955), and the Havana “Tricontinental” (1967).

Part of this broader genealogy of anticolonialism involves understanding how a largely European Marxist internationalism gave energy to later third world movements that attempted to resist both US and Soviet imperialisms during the cold war. This involved a concomitant shift in focus from purely political-economic analysis to analysis of the racial state, a shift evident in the work of Martinican revolutionary Frantz Fanon, who became the key theorist affiliated with the Algerian National Front (FLN) that overthrew the French occupation. Fanon’s persistent focus on race was diminished in some corners of academic postcolonialism in the 1980s and 1990s, and has returned to the center of postcolonial analysis of American empire in more recent work.

The famous essay “On Violence” from Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth highlights connections between colonial racial violence and the earth — situating the violence of colonial settlement in the splitting of social and ecological worlds, the manufacturing of waste, the affective experience of violence, and the rendering of the colonized into zoological figures. It is my hope that Fanon’s figure of the ‘wretched of the earth’ as a form of management of ‘species’ can help to ground a more recent text: Dipesh Chakrabarty’s already-classic essay “The Climate of History: Four Theses.” In the spirit of reviewing and testing the limits of postcolonial knowledge projects informed by historical materialism, Chakrabarty reviews the climate change literature and asserts that climate change cannot be fully grasped by a political discourse focused only on an account of inequalities produced by capitalism. Chakrabarty argues for a form of species-thinking that can capture how human beings’ form of life is determined by geophyisical conditions of the planet that exceed the parameters of political-economic form. How does this argument square with our prior discussions about climate as a racial assemblage? Or about the potential pitfalls of turning from human to nonhuman objects? How are ‘human’ and ‘species’ defined for Chakrabarty? Does this square with Fanon’s presentation of colonialism as a Manichean struggle between ‘species’ of man?

Naveeda Khan’s ethnography of chauras (silt island dwellers in Bangladesh) throws Chakrabarty’s essay into relief from another vantage — one of a glorified ‘adaptation’ to climate change. How does Khan situate the narrative of the death of nature (such as Weisman’s cited by Chakrabarty) as an element of environmental governmentality in the era of global warming? One track Khan pursues is to reflect on scale, to think about how global narratives of climate change inhere in microprocesses of destruction that multiply make up the experience of disaster. Is the position of the chauras one in which we glimpse the precarity of the human-as-species? Or does Khan offer an alternative way of conceiving the networked actancy of earth and climate-affected itinerant farmers? Think about Khan’s method — how does she describe how she approaches ethnography and what is the significance of its relationship to gender in the work of Veena Das? As potential environmental subalterns, the chauras force upon abstract invocations of planetary crisis the question of specific structural positions of peoples affected by climate disasters. Jodi Byrd’s opening essay in this group of texts queries whether postcolonial theoretical turns to vitalism and affect in an era of environmental crisis accomplish a ‘transit of empire,’ a dependence on the figure of the paradigmatically ‘vanishing Indian’ as the pivot to the planetary future of empire.Do critical narratives of ecological crisis instantiate an orientalism that takes the vanishing native as paradigmatic figure of human futurity? How do we resolve the different scales of analysis in anthropocene humanities with specific attention to lived experience and the differential production of environmental precarities and adaptations?

MEETING #3, 23 JANUARY 2015

Seminar recap: Today our discussion of ‘earth’ focused largely on the essays by Chakrabarty and Khan on climate change. Both essays begin by citing a pop-science text that envisions extinction, although their arguments diverge widely in how to respond to the sense of crisis generated by such texts. We discussed Chakrabarty’s argument for a species-thinking in order to grasp the political urgency of climate change and the geophysical agency of humanity. We also reviewed his argument about the insufficiency of a narrative of capitalism in grasping what he proposes are geophysical boundary parameters of the planet that preexist capitalism and socialism. This involved discussing the different possible temporal frames for ‘anthropocene’ and the possibility that ‘boundary parameters’ for human life might not be evenly distributed across the planet. We also discussed Chakrabarty’s arguments in light of his prior work on historicism’s enfolding of subaltern experiences of labor into a totalizing history of capital, noting that the new work on climate allows him to turn from historical difference to a new figure of human universality based not on identity but rather on shared risk. In light of some lingering concerns and questions about all of these moves — which seemed divorced from the political mobilizations of transnational environmental and indigenous movements — we turned to Khan’s essay and noted its focus on smaller scales of relation; here ‘climate change’ is broken up into constituent processes and geophysical agencies are localized in the actancies of the river. We discussed how Khan’s ethnography navigates uncertainty in the distinction between weather and climate, generating specific scenes of ‘adaptation’ that suggest that crisis is an everyday reality rather than a coming spectacle. We also puzzled over the specter of Sabine’s suicide at the end of the essay, which both resonated with the problem of the subaltern going back to Spivak and with an everyday sense of a dying nature that Khan referenced at the beginning of the piece. These discussions of Chakrabarty and Khan helped to illuminate Fanon’s use of ecological and species metaphors for decolonization, which might be read as refusals of a politics of liberal recognition.

The readings in the coming weeks will have us zero in on more specific topics concerning nonhuman bodies and agencies. Narrowing from the universe of ‘matter’ and the geophysical realm of ‘earth,’ our next meeting (6 February) will explore life (in the biological sense of the word). Although we will center our conversations on human-animal relationships, I have selected the broader keyword ‘anima’ as it both echoes ‘animal’ and indicates a broader field of relationality involving the animate domain, a field that we might characterize as ‘affective.’ I hope to situate our discussion of animals and animalities at the crossroads between vitalism (Bennett; Deleuze and Guattari) and the biopolitical theories of Michel Foucault.

Foucault was primarily concerned with the life of humans, but his theory of biopower suggested that modern regimes of power took on the reproduction of the human as species as the privileged arena of governmental intervention. Foucault traced biopower through the histories of the prison and the mental institution, the discourses of sexuality, and efforts to contain viruses and bacteria, which allow us to consider his work from an interspecies perspective. Foucault distinguished the development of biopower from classical understandings of the power of the state as inhering in the power to kill or let live; Foucault sees modern liberal states as engaging in a number of disciplinary regimes centered on controlling bodies and populations beginning in the 17th century. These shift the emphasis of power to from making die or letting live to making live or letting die. This, of course, differs from Fanon’s account of colonialism as suffused with sovereign violence; Foucault is interested in the more subtle machinations of power captured through inclusion, recognition, and subjectification. So through biopower, Foucault contends that modern government exercises force by governing through knowledge and the production of subjectivities rather than only through exercising domination over individuals; power can be seen as productive rather than simply repressive. (Foucault also suggests that sovereign and disciplinary power can overlap; it does not have to be a simple historical succession from one to the other.)

We will consider different approaches to extending Foucault’s theory into the domain of nonhuman animal life. Animals were largely absent in Foucault’s work; however, a number of recent studies of human-animal relations foreground Foucauldian frameworks to understand how humans and other species are entangled in fields of biopower. The two more substantial readings for the week both claim to utilize a biopolitical approach to the cultural study of human-animal relations. However, their methods for doing so diverge because they each have different approaches to understanding materiality. Mel Chen’s book Animacies theorizes that ‘animacy hierarchies’ built into language systems work to classify different species of matter and life as more or less lively, a phenomenon that gives form to unequal power relations by differentially investing bodies with value. According to Chen’s vitalism, particles of lead can be just as lively as life forms given that they mobilize affective relations across political and species borders. The Chen reading will specifically explore how animal vitalities (especially figures of metamorphosis) are taken up in discourses of race and sex. While Nicole Shukin’s book Animal Capital similarly pays attention to animals as both bodies and figures, Shukin explores biopolitical relations through a Marxist frame that connects fantasies of neoliberal mobility to the material logics of industrial animal rendering. Because of their unique approaches to the materiality of the animal (Chen’s vitalism and Shukin’s ecological Marxism), these books in some sense stand apart from mainstream work in the burgeoning field of ‘animal studies.’ It is my hope that they may allow for some ways forward for postcolonial and critical race scholars who sometimes remain skeptical of current scholarship on animals and animality.

Much recent scholarship has recently highlighted the so-called ‘question of the animal,’ which is usually posed as a philosophical question about what it means that animals have been excluded from the realms of subjectivity and representation in modern political and ethical discourse. Foundational books on ‘the question of the animal’ in philosophy have been published by Jacques Derrida, Giorgio Agamben, and Matthew Calarco, while Cary Wolfe, Anat Pick, Kari Weil, and Donna Haraway have published the key books that extrapolate the implications of this ‘question’ for cultural studies. Some of this work highlighting the roles of nonhuman animals in literature, history, and politics has been invigorated by the rise of liberal animal rights philosophy in the US and Britain since 1970 (see classic writings by Peter Singer and Tom Regan and more recent works by Gary Francione, Paola Cavalieri, and Steven Wise), although ecofeminism and feminist science studies have long included discussions of human-animal relations and theories of interspecies embodiment (see Carol Adams, Donna Haraway, Vinciane Despret, Val Plumwood, and Deborah Bird Rose). There is also a growing literature exploring industrial animal agriculture; Timothy Pachirat and Noelle Vialles‘ books explore the hidden assumptions and evasions in the spatial structures of slaughter, following classic works on the topic such as Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle and John Berger’s important essay “Why Look at Animals?”

Yet ‘animal’ is a term that poses its own problems. On one hand, the category ‘animal’ remains unthinkably broad, as Jacques Derrida has suggested; he coins the term animot to signal the multiplicity of species and sexes that can only be violently resolved into a contained identity in a mot, a word (“animal–what a word!”). On the other, much European humanist philosophy has turned on distinguishing human from animal, making the very figure of the animal significant to the development of colonial ideas about subjectivity. In some cases, animal studies scholars generalize about the link between anthropocentrism and racism, with Cary Wolfe suggesting that racism is simply an instance of a broader structure of anthropocentrism in the introduction to his book Animal Rites.

While such generalizations foreclose important critiques of racism and colonialism associated with animal rights and welfare activisms, they do offer starting points for considering situated colonial human-animal relationships. Following Fanon, a number of postcolonial theorists (notably Achille Mbembe and Graham Huggan and Helen Tiffin) have theorized (neo)colonial power via the management of species axes such that colonialism appears to defend the human against the animal specter of filth, disorder, indignity, or violence. Colin Dayan has written about the use of animals in law to justify an expanding the racial state’s violent uses of incarceration. What, then, are the possibilities and limits for thinking ‘the animal’ decolonially? There is growing attention to animals among scholars reflecting on (neo)colonialism, evident in works by Anand Pandian, Leela Gandhi, Lauren Derby, Clapperton Mahvunga, Sara Salih, Juno Parreñas, Jake Kosek, Renisa Mawani, and Naisargi Dave, as well as in a burgeoning literature in colonial environmental history.

As Kim TallBear’s lecture that we will view online suggests, indigenous scholars have also long reflected on animal-related questions without necessarily posing animality as its own universal field opposed to the human. In an unpublished lecture, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has suggested that magic realism has become such a dominant novelistic mode for postcolonial literature in part because it is able to integrate different indigenous traditions and experiences of time, space, and species into a form of representation that travels. M.K. Gandhi’s extensive and sometimes contradictory writings on animals (example) attempted to grant them ethical recognition while also denominating responsibility to animals, such that they could be incorporated into the developmental needs of the post-independence nation.

These varied race-critical and postcolonial perspectives on animals and animality appear at a time in which states are granting expanded rights to animals, companion animal consumer economies are reaching unprecedented scales across different national locations, animals are conscripted into warfare, and biomedicine is increasingly investing in and engineering animal tissues for medical use. So as we pursue understanding the biopolitics of contemporary and historical animal life — the ways in which animal bodies are folded into projects of governing bodies and populations — it will be necessary to account for both violent uses of animals in slaughterhouses and other sites of biocapitalism while at the same time attending to the fact that neoliberalism increasingly invests in animals and human affection for them as sites of value and accumulation.

MEETING #4, 6 February 2015

Last week’s seminar on anima/animal was in some sense the most difficult to process so far. Although in comparison to the wild speculative realities of OOO and vitalism, animal studies may appear rather unsexy, it seemed that the cultural studies methods of Chen and Shukin went in a different direction than earlier readings; it became, surprisingly, difficult to transition back from the worlds of matter and planet to the domain of ‘culture’ as well as to the more familiar terrains of ‘intersectional’ analyses of social difference through human-animal relation. Perhaps this is partly due to the widely different approaches to materiality in Chen’s Animacies and Shukin’s Animal Capital, as well as to the denseness of both texts. We spent some time working through the problem of affect in Chen’s text, but affect’s broad orientation became a problem for reading the chapter on transubstantiation; it seemed difficult for participants to toggle between ‘real’ and ‘figural’ animals, especially as the critical object rapidly shifted between trans embodiments, racialization, and human-animal encounter. It seems that transubstantiation gestured toward a methodological incorporation of the embodied and technical logics of affect (located respectively through bodily physical entanglement and different kinds of media) without pinning it down in a didactic way. So the method and writing style may have caused some translational issues here, but beyond that we also seem to be working through a lack of clarity about how affect theory does or does not differ from vitalist approaches, or perhaps where its specific content lies. Shukin gave us something more concrete on these questions, explicitly linking the industrialization of animal capital to the circulation of animal figures in media; for Shukin, the mimetic capacities of animals (their attributed ‘nature’ situated in the fetishistic fascination with animal affect) represent a particularly potent symbolic matrix for neoliberalism’s attempts to naturalize exchange based on the exploitation of human/animal/nature. But this was a very dense and challenging reading, one that confronted us with some more established concepts in Marxism (fetishism, alienation, mimesis) as well as contemporary debates about affect and neoliberalism. Shukin thus brilliantly captures an ecological socialism that is attentive to both matter and meaning. If this felt too abstract for unfamiliar readers, Shukin insists that her own method is materialist in a way that idealist animal studies theories (esp Derrida, Lippitt, and Deleuze) consistently avoid to their own detriment.

Our discussion of the keyword ‘Anima’ opened some questions of method in relation to new-materialist analysis. Chen’s book is pathbreaking in that it aims to square queer studies, animal studies, and environmental cultural studies with the biopolitics of race, sexuality, and disability. Chen seeks to do a cultural analysis that integrates inhuman actants with human questions of domination and inequality. This involves some sense of historicity in order to situate claims about where power lies. Yet while Chen placed analyses of cultural objects within specific contexts of production and dissemination, Shukin asks us to consider historicizing the very theoretical tools we use to do the analysis; can an object such as animal, animacy, affect, or nature can be so readily theorized on a broader, abstract level? Against some tendencies of idealist animal theory that takes the animal as generically oppressed in hierarchal social relations, Shukin “struggles… against the abstract and universal appeal of animal and capital, both of which fetishistically repel recognition as shifting signifiers whose meaning and matter are historically contingent” (14). This realization also extends beyond the living organism to the broader field of affect that Chen intends to recuperate in order to trace the materialization of social hierarchy. While Chen is explicitly interested in the uptake of affect in forms of social power and domination (distinguishing Animacies from the vitalism of Bennett), this could still run into problems because animal affect might be the very privileged site at which neoliberalism works to recede into the domain of nature: “affect as an authentic animal alterity is impossible to distinguish from the intensities unleashed by capitalism” (Shukin 32). Shukin glosses a variety of conditions of contemporary capitalism that have us asking this question regarding affect. Some of these include the post-Fordist rise of information economies, the feminization of industrial workforce, and the rise of affective labor, or ‘service with a smile.’ Emerging biocapitalisms (Sunder Rajan) and the articulation of an affective form of securitization after 9-11 also seem to be contributing factors to understanding why there is a turn to affect in contemporary critical theory.

The questions raised by this crossing of Chen and Shukin’s books on animals and affect have important effects that we will trace next week through the two keywords of ‘affect‘ and ‘security.’ Because affect appears to circulate in animal studies works, because it also seems aligned with vital capacity and transformation rather than with stasis or identity, there are a number of questions we could ask to further specify the content of affect. Jasbir Puar’s essay on affect and disability is a starting point for thinking through this. Puar raises the question of whether affect is primarily associated with bodily capacity — with circulation, movement, and transformation — and thus wants to think through the problem of debility or bodily impairment for affect studies. To do this, Puar takes us in some directions that are unique for someone doing work on either affect or disability. Puar situates the apparent liveliness of affect within the domain of ‘living in prognosis,’ living within capitalism’s statistical idea of a certain normative lifespan and body outcomes. This suggests that medicine and biocapitalism are invested in securitizing a managed time frame in which certain body capacities slowly wither and fall away; despite this managed transition of debility, living in prognosis nonetheless generates hope or affective investment elsewhere — in biomedical apparatuses, in struggle to overcome disability, etc., although these sites of hope are cross-cut by other social factors, most notably race, where time itself is constrained by the threat of premature death. This is all to say that affect emerges unevenly within neoliberal processes of biopower and necropower that constrain and reproduce bodies and populations across varied social ‘events’ such as race, sexuality, debility, etc. as they nonchalantly distribute death.

Puar’s essay is somewhat speculative (the book version should be coming out soon). One issue it raises but brackets is the question of why affect now?… What is affect and what are its different genealogies? And which versions of affect are privileged in the so-called affective turn? Let’s step back for a minute and see if we can provisionally define affect, if we can come up with some content for it, and perhaps begin to evaluate its deployment in new-materialist work.

In lay contexts as well as in professional psychiatry, affect is commonly viewed as synonymous with emotion. In behavioral psychology, especially in the US tradition led by affect theorist Silvan Thomkins and developed in the more recent work of Paul Ekman, affect denotes a specific number of contained and universal emotional responses that an individual can have to phenomena, revealed by bodily gestures such as facial expression. They are enumerated in lists and separated into ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ affects; Ekman, for example, lists ‘amusement’ and ‘shame’ as positive and negative universal affects, respectively. Affect in the behavioralist tradition is also commonly linked in the ‘ABC’ heuristic of affect, behavior, cognition, which ties together the reactivity of the autonomic nervous system to bodily expressions and to sensory perception and conscious thought. As such, behaviorism is interested in the ways in which affect leads to subjective moods, dispositions, behaviors, and thoughts, generally among humans. Given this largely Cartesian view of the machine-like characteristics of affect, it is no surprise that critics of affect theory like Ruth Leys have viewed the field as inherently essentialist in its attempt to return from constructivism to a realism of the body.

Yet there are other traditions of affect that look different. Let’s first stay within psychology. Freud had an incomplete theorization of affect, and generally used the term when referring to stress or anxiety. In a case of ‘hysteria,’ for example, Freud described a psychological paralysis that occurred because a specific limb — an arm in this case — was somatically functional but traumatically blocked by an excess of affect such that only removing that affect — that quota of psychic investment in the traumatic object — was the subject able to free the arm. (This description is analyzed in Ranjana Khanna’s eye-opening essay ‘Touching, Unbelonging, and the Absence of Affect’). You may recall such a vision of affect in Fanon’s description of decolonization in ‘On Violence.’ Fanon writes that under colonial stress, the colonized build up an excess of energy that is finally unleashed in the frenzied moment of decolonization. Like for Freud, for Fanon affect is generally a subjective somatic state characterized by friction between the subject and the world worked through the state of trauma or other site of psychic investment in an object. Given Puar’s interest in a disability-critical analysis of affect, this Freudian view of affect as debility is especially interesting. Affect appears not so much as a pre-given emotional response or capacity but rather as the somatic materialization of a negative emotional state. And that materialization is profoundly disabling in this instance. At the same time, the question of affect’s content in general is postponed; it is a manifestation that is asserted in a specific case without generalization. Nonetheless, like the behavioralist approach Freud’s seems to posit a positive/negative binary for understanding affect based on a taxonomy of emotions.

Yet we have still not glimpsed the diversity of approaches to affect. As a vitalist, Deleuze uses affect without reference to the hydraulics of subject-formation and the Cartesian dualism of the mind-body split. Affect appears to be the pure potentiality of bodily transformation, movement, and capacity. It is immanent to all life, not just vertebrates who possess a central nervous system. It may also be a characteristic of assemblages, including those incorporating nonliving bodies. So even though Deleuze is deeply suspicious of Cartesianism, there appears to be an essential capacity of the body to affect and be affected by other bodies that Deleuze hopes to trace as pure potential. There seems to me to be a strong resonance with this view of affect in Chen’s work; despite the fact that Chen explores some contexts of boredom and waiting under mercury poisoning, even here there is an ‘incredible wakefulness,’ a vitality that appears to characterize affect. So one concern that might posit or explore about Chen’s approach to affect is whether it tends toward vitalization even if the method of the book explicitly claims to also explore violence, power, and slow death. This may further resonate with postcolonial critical concerns about a certain cosmopolitanism of affect, about its ability to circulate across and beyond bodies in seemingly magical ways.

Shukin’s original query, developed by Puar, was to consider whether affect was the privileged site of neoliberal accumulation rather than a site of becoming or queer potential. This much has been suggested by two important Marxist interpretations of affect influenced by Lacan and Deleuze. The first, in Frederic Jameson’s ‘Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,’ attributes to the so-called postmodern age a ‘waning of affect,’ a loss of the subject and its emotional depth and a turn to surface intensities. Of course, Jameson is using affect conventionally and conflating it with emotion; from a Deleuzean perspective, it is the surface intensity he denounces that would be the site of affect. Nonetheless, his point is clear — postmodern culture loses its sense of history and its narrative form that inscribes emotion and its resistant political potentials in the name of fleeting and immaterial cultural forms. If Jameson seems especially nostalgic for modernism and its attendant cultural forms like the historical novel, the works of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri are more interested in thinking about the specific ways in which affect generates political economic forms of relation under ‘Empire.’ Hardt and Negri posit that ‘affective labor’ — the labor of the service industry, represented by the imperative to provide ‘service with a smile’ — is one of three primary forms of immaterial labor generated by neoliberalism. Affect thus has no materiality other than the intensity of the relation between capitalist subjects.

Interestingly, in all of these approaches to affect — the behavioralist, the psychoanalytic, the vitalist, and the Marxist — appear to rest upon the assumption that affect is characterized by surface/depth binaries. This is so even when vitalists and Marxists dispense with the positive/negative emotion binary that allows emotional capture to seep into the definition of affect. As such, there is a consistent risk that affect theories take affect as the fleeting, contentless, or immaterial specter of the work of some other process, whether it be emotion, behavior, cognition, or accumulation. Can we attribute some specific content to affect? In my own work, I’m trying to think about whether, if the bodily materiality of affect appears obscure, it is possible to glimpse the materiality of affect in its varied forms of biopolitical uptake or capture. These might happen in the political management of emotions, but also in other systems of bodily interface such as biosecurity or economic security projects. So, thinking with Shukin and Puar, if the biopolitical investment of hopes in biomedical technologies, animal mobilities, or human-animal war machines a site at which we can give a more particular account of how affect is mobilized, governed, and reproduced through broader social relations?

So the readings for next week will help us think through this problem. When affect is the material site of governance, it would appear that we break with the siting of power in the subject at the Foucauldian intersection of knowledge/power; Massumi’s article, for one, argues that we’ve entered an era of ‘environmentality’ in which the unpredictability of affective relation makes risks or threats to security a generalized feature of the environment, and thus uncontainable by traditional strategies of discipline or normalization. Politics becomes reactive and oriented toward the unknown phenomena that emerge rather than known or quantified threats. Speculation is conjoined with the shift from threat to risk. This problematic, then, involves circulation of bodies and affects, which may require us to rethink the idea of affect as bodily capacity, which seems to jive with visions of neoliberal circulation. In her article on ‘Security Bonds’ for next week, Shukin quotes Foucault from the lecture series Security, Territory, Population on this very point:

freedom is nothing else but the correlative of the deployment of apparatuses of security. An apparatus of security … cannot operate well except on condition that it is given freedom, in the modern sense [the word] acquires in the eighteenth century: no longer the exemptions and privileges attached to a person, but the possibility of movement, change of place, and processes of circulation of both people and things.

This definition of freedom as ‘the correlative of the apparatuses of security’ is an interesting and seemingly counterintuitive definition. In a post-911 world, we might normally think that security is about locking down the movement and capacity of dangerous bodies, of creating stable borders and identities, of fetishizing that which is to be securitized: the human, the nation, whiteness, wealth… all against the specters of circulation that would seem to compromise security. But if security melds with liberal visions of freedom, and thus takes on the imperative of circulation, then security may take on the very form of the generalized envioronmental threat that Massumi described. This is one direction that Melinda Cooper goes in her article on biosecurity and the war on terror — the goal is to preempt emergence of new biothreats, but this does not mean containment; it means aggressive counterproliferation, the use of the form of the threat to constantly interrupt and shift the grounds of war itself. Thus we have a new set of thematics to consider in relation to the shifting ground of neoliberal warfare and the Deleuzean war machine — when we talk about war in the post-911 moment, where is it located if it takes place in the environment and if the technologies of government appear to mimic the range of embodied capacities of that environment?

These are big questions, and they reflect major issues about race and disability, but also about whether certain narratives we’ve been constructing about the new mateiralisms hold water. Is it true that indigenous traditions of habitation in the realm of nature or environment simply preexist and prefigure these arguments about the mutating environments of neoliberalism? I am suspicious that an analysis like TallBear’s of exclusion of native epistemologies works to analyze the ongoing processes of settler colonialism in the emergent forms of warfare. Byrd was perhaps more useful in shifting our historical register to consider early settlement of the Americas as the original site for the elaboration of discourses on terrorism. Nonetheless, the turn toward human and environmental security in the war on terror will have some interesting resonances with indigenous critique because the very land claimed in indigenous sovereignty struggles or in processes of subaltern climate adaptation appears to be the material with which the state works to conceptualize security. How might we return, then, to Naveeda Khan’s article and to Sabine’s suicide as a way of conceptualizing security in a world of proliferating risks? And how do topics raised in next week’s readings, like the weaponization of dogs and the use of weapons proliferation to gain strategic advantage over bioterrorism, relate to broader geographies of colonialism, racism, and neoliberalism that we analyze in our work?

(note: links to secondary texts are not active yet for these last two current entries. i will get to this later in the semester. feel free to email me if you need citations.)

The visit with Renisa Mawani extended our conversations about affect theory. Participants raised some questions about the concept of ‘atmosphere’ in the seminar. Is it particularly connected to race, or does it work equally well for other axes of social difference? How does the theory integrate the geospatial and affective registers of the term? Some of these questions/discussions relate us back to the content of affect (where is affect located, how can it be identified outside of a subjective narration of experience), others to problems of scale (how to represent sets of interactions that take place unseen, beneath the skin), and still others problems of method (how to go about describing an atmosphere, explaining all of the aggregated flows that go into it). These questions remain open but suggest that the concept of atmosphere may be ripe for doing particular kinds of spatial readings of race in context (perhaps not wholly substituting for Omi and Winant’s racial formation theory or other structuralist approaches to understanding the power dynamics of race). We discussed briefly how Kathleen Stewart, Lauren Berlant (via Deleuze), and Fanon deploy the term atmosphere. The resonance between the idea of a racial atmosphere and a warming climate was one that interested some participants — both are sites of violence but they seem to work according to different logics. It would be interesting to see where the warming atmosphere intersects with the racial atmosphere.

On the other hand, our readings on the keyword ‘carbon’ suggest that in addition to the atmospheric, the fluid above-ground relations catalyzed by ecological and social process, it might be necessary to dig down to the subterranean to capture the complexity of planetary connections in the so-called ‘anthropocene’ — especially since climate change is a process that is deeply linked to the political economy of oil. On this point, despite their wide divergence in method and genre, Timothy Mitchell and Reza Negarestani seem to agree that carbon names a set of materials that lubricate both forms of neoliberal capitalism and ‘political Islam’; both authors see capital, oil, and political violence as intimately related, captured in their concepts ‘McJihad’ and ‘Gog-Magog Axis’. Mitchell, who describes his project as a crossing between postcolonial theory and science and technology studies, seems to follow Latour’s actor-network theory in conceiving of oil as a particular type of political actant. Negarestani, on the other hand, is interested in how the form and affective quality of oil opens political undercurrents; this is a speculative-realist approach in line with Morton and Harman and influenced by Deleuze and Guattari. In Cyclonopaedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials, Negarestani’s experimental philosophy-fiction suggests specifically that oil is a ‘narrative lubricant.’ In fact, Negarestani’s descriptions of the material forces catalyzed in oil route death into life, past into future, enlivening different political configurations and standpoints: ‘oil as hydrocarbon corpse juice is itself a mortal entity which has been the source of ideology for petro-masonic orders and their policies — from OPEC to the agencies of War on Terror to pomo-Leftists.’ (27) Both authors, in fact, suggest that certain types of representation (ideology, perhaps theory) may be an effect of the material relations catalyzed by oil without conscious awareness of that dependency.

In the chapters of Carbon Democracy beyond what we read in ‘McJihad,’ Mitchell makes a number of key points about the relationship between oil and democracy. He describes a historical shift from coal (which enabled the Russian revolution and other worker-based social movements) to oil which shuts down labor resistance due to pipelines and top-down control. He also describes relationships between the oil economy and the rise of economics as a science (including its neoliberal theories). Mitchell also discusses the transcendence of peak oil by unconventional carbon resources (fracked/cracked hydrocarbons that allow capital take on the geologic processes of earth). One of the main empirical contributions of Mitchell’s book is to clarify — against commonplace arguments on the Left (see Harvey, The New Imperialism) — that much of the colonial effort to control oil has been with the goal of shutting down production, which enables high prices that are at the heart of the oil-arms nexus of US policy in the Middle East.

The readings on carbon have a close tie-in to Foucault’s journalism on the Iranian revolution. We discussed how Foucault underwent a so-called ‘ethical turn’ following his biopolitical writings, and how this turn occurred in the tumultuous contexts of the end of the Vietnam War, oil shocks and the rise of the Iranian revolution, and the emergence of US-led neoliberal market reforms at the end of the 1970s. In both his writings on Europe and Iran, Foucault seemed to turn from biopower to pastoral power, from an account of power in life to one of political will and even political spirituality in his accounting of subaltern ethical counter-conducts. Foucault was roundly criticized for this in France, as explained by Afary and Anderson in their book on Foucault in Iran. Their book, as well as Melinda Cooper’s article on Foucault and neoliberalism (‘The Law of the Household,’ available through her website), both see Foucault as embracing a conservative turn toward masculinist visions of ethical self-sacrifice in religious conduct. Nonetheless, there are other critics who offer defenses of Foucault’s journalistic writings on Iran (see Babak Rahimi’s review of Afary and Anderson, https://networks.h-net.org/node/6386/reviews/6694/rahimi-afary-and-anderson-foucault-and-iranian-revolution-gender-and).

These debates focus largely on issues of gender and secularism. Yet given the important role that oil strikes play in Foucault’s accounts of the revolution, it might be useful to follow Rahimi’s insistence that Foucault articulates a critique of modernization in these writings on Iran. Why don’t oil strikes lead Foucault to a greater consideration of the politics of carbon (and, thus, potentially, of climate and environment) in the evaluation of the revolution? If Foucault had articulated an antihumanist account of the human in the theory of biopower, what is reflected in his turn to the postsecular? Can postcolonial critiques help to articulate the connection between the posthuman and the postsecular that are evident in Foucault’s late critical trajectory?

We may have a stronger vantage point on these questions when we return to the postcolonial critique of the ‘human.’ Whereas many of our texts this semester have focused on the problem of anthropocentrism, this is not the same thing as humanism. One of the tasks of postcolonial theory has been to track the insidious violence behind the materialization of liberal-humanist political forms, such as those that assert universal human equality through colonial regimes of property, citizenship, and rights. Drawing on and expanding feminist frameworks for understanding how such forms of power inhere in the bodily and geographic domains of the intimate, Lisa Lowe integrates an understanding of how forms of revolutionary, bourgeois, and transcolonial intimacy are policed and integrated into humanist figures of the propertied subject of global capital in her essay “The Intimacies of Four Continents.” It is fascinating to me that Lowe begins by noting that sugar is creole. What can we do with the analysis when we sharpen focus on the inputs of racial energies (slavery, indenture) as well as other mercantile energy flows (solar through photosynthesis, wind through atlantic shipping, and animal labor) into a nonhuman species that became the key atlantic colonial commodity?

Yet we have still struggled to hold together interspecies critique with postcolonial efforts to critique the fissuring of the human through forms of social power. (See the earlier discussion of ‘anthropocene.’)

So to what extent are there resources from within the postcolonial critique of the human for an apprehension of the posthuman? In addition to Lowe’s visit, we will consider three prominent texts in the field. Spivak’s essay does not directly suggest a turn to nonhuman bodies, although interestingly it has occasionally been appropriated in animal studies and enivronmental humanities to characterize the inscrutable ecological ‘subaltern.’ It speaks directly to poststructuralist issues of speech and language that commonly arise in animal studies, for example in the works of Derrida and Wolfe.

Spivak’s famous question about whether the subaltern could speak actually begins with some of the very tensions we’ve discussed throughout the semester — an attempt by Deleuze in particular to grasp realism. For Spivak, D&F’s narratives suggesting the transparency of the worker or the Maoist revolutionary are disingenuous because they disavow the positionality of the intellectual in the international division of labor (the privileged position that allows him to read the subaltern, to conflate the desire and interest of the third-world revolutionary subject).

But could it reasonably be said that Foucault and Deleuze do the opposite? That they invoke the transparency of the subaltern not to burnish their own stature to read what counts as revolutionary but to refuse the demand that they, as western intellectuals, perform the translation? Do they want to assert that third-world revolutionaries speak to their own societies in context and don’t need to be approved by intellectuals divorced from their movements? That might be consistent with Foucault’s interview with Parham from last week. D&F might then insist that they are attempting to locate themselves in the networks of radical practice, while Spivak is simply content to deconstruct the humanist ideal of speech to a point of silence. Deleuze characterizes Foucault’s work on prisons as revealing ‘the indignity of speaking for others,’ which seems like it resonates with parts of Spivak’s essay. This line of thought might be suggested if we give Foucault more space to fill out his thought than Spivak affords him in her short quotes from the conversation “Intellectuals and Power”:

the intellectual discovered that the masses no longer need him to gain knowledge: they know perfectly well, without illusion; they know far better than he and they are certainly capable of expressing themselves. But there exists a system of power which blocks, prohibits, and invalidates this discourse and this knowledge, a power not only found in the manifest authority of censorship, but one that profoundly and subtly penetrates an entire societal network. Intellectuals are themselves agents of this system of power-the idea of their responsibility for “consciousness” and discourse forms part of the system. The intellectual’s role is no longer to place himself “somewhat ahead and to the side” in order to express the stifled truth of the collectivity; rather, it is to struggle against the forms of power that transform him into its object and instrument in the sphere of “knowledge,” “truth,” “consciousness,” and “discourse.”

Whatever we think of Spivak’s accusation about D&F’s complicity with the capitalist international division of labor, Spivak’s essay directs important attention to the heterogeneity of colonial power. Shifting historical/geographic frames in later sections of the article, Spivak discusses the colonial prohibition of sati (wives’ suicides upon their husbands’ deaths) which worked to justify colonialism as ‘white men saving brown women from brown men.’ (We had discussed Khan’s representation of an imagined climate-related suicide in Bangladesh that we might return to now that we’ve read Spivak.) Spivak’s is a difficult argument, and one of the problems pointed out by many South Asian feminist critics (see Ania Loomba’s summary of the debate) is that the example of suicide by necessity will suggest that the colonized woman cannot speak. With all of these difficult issues nestled in this one essay, there has been much debate and confusion over the piece. Overall, we can say that by parsing apart aesthetic and political representation, Spivak attempts an antihumanist rendering of colonial resistance, one much different than Fanon’s earlier assertion of a necessary and inevitable colonial speech at the moment of decolonization, wherein the colonized ‘roar with laughter’ when they are called an animal. Here, the Derridean deconstruction of the subject and of language is paramount for understanding the contradictions of the colonial subaltern, shot through as it is with the power architectures of social difference.

Achille Mbembe’s much more recent article on ‘Necropolitics’ offers some interesting echoes of and departures from Spivak. While the productivity of suicide in Spivak’s essay resonates with Mbembe’s power through death, Mbembe focuses on the category of human moreso than subject. The human/animal divide is central to understanding why death takes on a certain kind of force, traced from back to the plantation all the way to contemporary war machines in Africa and the three-dimensional Israeli occupation of Palestine. (Unfortunately, his reading of Foucault via Agamben seems idiosyncratic, a point convincingly argued in the opening pages of Lauren Berlant’s essay on slow death.) Mbembe has moments of ecological vision in this piece, including the discussions of attacks on infrastructure and chemical plants. Consider also how Mbembe might relate to Negarestani, who characterized oil as ‘corpse juice.’

Dipesh Chakrabarty offers a different approach to grasping the forms of life and knowledge that fall away from the totalizing abstractions of European (post)-Marxism. In his book Provincializing Europe, Chakrabarty gives a searching foundational critique of subaltern studies historical scholarship (including his own earlier book). At a moment when postcolonial studies had reached the zenith of its world academic influence, Chakrabarty gave a rather sober assessment of the field’s desire to set aside the weight of European thought. Bringing us back to last week’s discussions of the postsecular, Chakrabarty in this chapter suggests that the agencies of spirits and gods represent a more-than-human element of labor practice in Indian factories that gets abstracted away in Marxist accounts of capitalism’s totalizing power. The link between this earlier moment of the postsecular with Chakrabarty’s more recent work on climate has not been lost on postcolonialists — in fact, Ian Baucom attempts to integrate the deep time of geology into Chakrabarty’s schema of multiple histories. How do these two moments in Chakarbarty’s work compare? Do they contradict? Do they represent a persistent desire to leave behind the critical projects that subaltern studies initiated?

It’s been some time since we’ve had a regular meeting due to guest visitors and my brief absence. In the last several meetings we have turned from the analytic objects of posthumanism (including climate, animal, affect, matter, and security) to examine some of the key elements of the postcolonial critique of the human as articulated through the projects of subaltern studies and, more recently, through the lenses of transnationalism and necropolitical critique. We can discuss further in our next meeting how these postcolonial texts resonated or departed from posthumanist ways of framing geography, race, colonization/land, violence, and animality.